Special Feature DIC: Shaping a New Era

Maintaining Bread’s Safety, Convenience and Taste

The secrets of a long-beloved taste around Japan

Bread entered the Japanese diet in the Meiji Era, which began in 1868, when the nation began embracing Western culture. Bread became popular in Japan in the first half of the 20th century with the production of breads tailored to the local palate. Japan is now one of the world’s largest producers and consumers of bread. Yamazaki Baking Co., Ltd. has led the development of the nation’s packaged bread industry. DIC Plaza visited one of Yamazaki Baking’s plants to learn why its products taste so good.

Yamazaki Baking:

Japan’s Bread Market Leader

For many people in Japan, there is nothing like a slice of toasted shokupan (white bread), with its crispy brown crust, pillowy soft interior, and enticing aroma and taste.

Toast has become a popular choice for breakfast throughout households in Japan because it is so easy to prepare and enjoy. For this reason, and because of the increasing trend toward busy family members eating alone at different times, bread consumption in Japan has grown steadily. According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications’ Family Income and Expenditure Survey, the annual household outlay for bread per household (two or more persons) has exceeded that for rice since 2011. Today, bread is now a staple of the Japanese diet.

Growth in Japan’s bread market has been driven by Yamazaki Baking. The company started out in 1948 as a shop in Ichikawa, Chiba Prefecture, that baked fresh koppe pan (soft rolls similar to hotdog buns) on consignment for customers who brought in flour. The company subsequently expanded by deploying advanced equipment and technologies imported from Europe and North America. Today, Yamazaki Baking accounts for around 40% of the Japanese bread market. Its numerous long-selling offerings include Royal Bread, Double Soft and Lunch Pack. It is also actively expanding operations abroad, with a focus on Southeast Asia. Overseas successes to date include Roti Tawar Funwari, which has been a major hit in Indonesia.

Sponge and dough: The two-step method employed by Yamazaki Baking since day one

DIC Plaza visited Yamazaki Baking’s Musashino Plant in the western Tokyo city of Higashi-Kurume, to learn the secrets behind the great taste of its products. The plant, which occupies a site measuring approximately 50,000 square meters—around the same size as the Tokyo Dome—is one of the company’s principal suppliers for metropolitan Tokyo. The delightful aroma of fresh baking greeted DIC Plaza staff as they made their way up the walkway to the front of the plant, which was a hive of activity with trucks driving in to deliver raw materials and driving out to transport products.

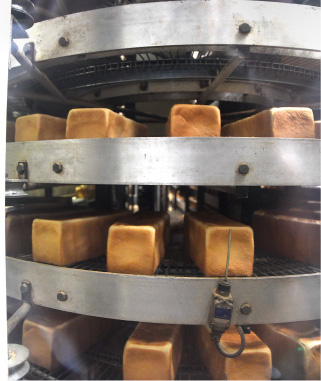

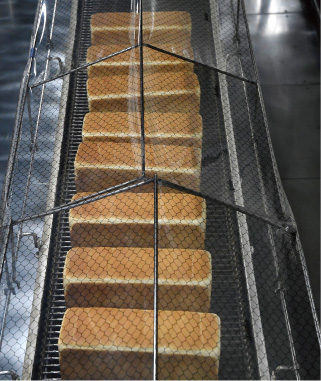

Once inside, the visitors were taken to see the sponge and dough process, the first stage of the shokupan production line, which features a giant kneader. Since its establishment, Yamazaki Baking has used the sponge and dough process, which involves making a sponge (yeast starter), which is kneaded and allowed to rest and ferment, after which the remaining dough ingredients are added and the final dough is kneaded again. This method is more time-consuming than the direct method, in which all ingredients are kneaded together, as it involves kneading the dough twice. The payoff, however, is a robust dough that not only delivers consistently soft texture and an enhanced aroma and taste, but also boasts stable quality and a superior tolerance to machine processing.

The sponge and dough process starts with the transfer of flour from a silo outside the plant into the kneader and the addition of water and yeast. Each batch is enough for approximately 1,400 shokupan loaves. The machine’s powerful stirring paddle combines and kneads the ingredients, after which the door opens and a huge lump of sponge drops out with an immense thud. The sponge is then moved to a fermentation chamber that maintains a perfect environment for yeasts to activate. Yeast fermentation produces carbon dioxide bubbles, which are trapped by the gluten network that forms as a result of the kneading of flour and water, causing the sponge to rise and filling the chamber with the aroma of alcohol, which influences the bread’s flavor.

humidity-controlled fermentation chamber for four hours.

is checked.

a second time and the resulting dough

is left to rest in a large container.

with carbon dioxide bubbles forming

on the surface.

alcohol and go through an air shower

before entering the production area.

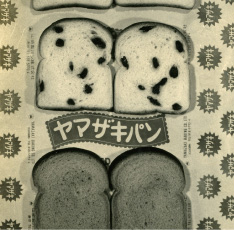

Yamazaki Baking started out in 1948.

fresh bread on consignment

for customers who brought

in flour.

opened in 1952, stocked

shokupan other products.

differentiated products by

color. Red was used for

standard shokupan,

purple for raisin bread

and green for brown

sugar bread.

made on an American-

manufactured production

line at the Musashino Plant.

Allowing appropriate fermentation time brings out the flavor of the flour

The sponge spends around four hours in the fermentation chamber, during which time it expands to approximately three times its original volume. It is then returned to the kneader and the remaining flour and water are added, together with secondary ingredients such as salt and sugar. The resulting dough is then kneaded vigorously. Part way through, the kneader’s door is opened a little so that butter or margarine can be added as kneading continues. When kneading is complete, the door opens and once again a huge lump of dough drops out. The second kneading develops the gluten, as a result of which a thin membrane can now be seen across the surface. This is what gives the bread’s its fine crumb (grain), ensuring that baking will result in a soft, fluffy texture.

“Making bread is kind of like raising a child,” says executive officer Takao Toichi, general manager of Yamazaki Baking’s Bread Production Control Headquarters No. 1, regarding the sponge and dough process. “People say babies who sleep well thrive. We build the bones of the bread by letting the sponge rest sufficiently in the fermentation chamber. During each subsequent production process, we shape and stretch the dough, after which we give it plenty of time to rest and rise. This repeated working and resting of the dough is the hallmark of bread making. This is what coaxes the flavor from the flour and creates the fluffy texture.”

A worker checks the color of shokupan loaves emerging

from the oven, the temperature and the baking time.

are shaped using a rounder.

formed into cylinders.

“M” shapes, placed in tins and proofed.

A job requiring craftsmanship and know-how gained through experience

The main principle of commercial bread production is to scrupulously manage temperature, time and measurement. However, because flour is influenced by everyday factors such as ambient temperature and humidity, as well as by location and season, kneader settings must be adjusted carefully to accommodate flour characteristics. Fine-tuning is also necessary during baking. Deviations in dough quality in the proofing period—the final rise before baking—will affect oven spring, i.e., the sudden increase in volume expansion of the dough in the initial stage of baking, so it is important to also adjust the baking time and temperature accordingly. “The taste of bread depends largely on whether you can develop high-quality gluten while the sponge rests and ferments,” says Osamu Nakahara, shokupan section chief at the Musashino Plant, commenting on process management at the plant. “This is something that we are very particular about. We owe our expertise in this and other areas to management techniques passed down by our predecessors. Many parts of commercial bread production lines today are automated, but much of our work still relies heavily on craftsmanship and know-how gained through experience, including minute adjustments necessary at each stage, from fermenting the sponge through to baking the loaves.”

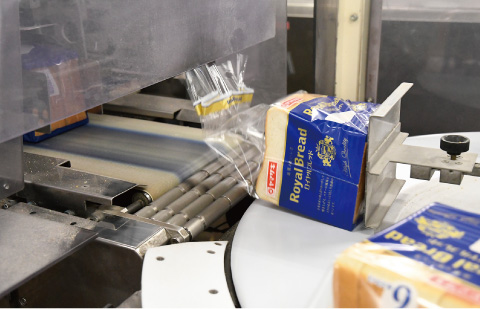

film into which the packaging machine has injected air.

making bags secure yet easy to open.

The Secret to Delicious Bread:

Coax the Flavor from Flour by Repeatedly Working and Resting the dough.

naturally and then transferred to a cooler.

about 100 minutes, after which the loaves

are transported to the packaging line.

three days before its expiry date.

Extensive quality management for superior food safety and sanitation

Another key requirement of bread production equally important to taste is exhaustive quality control that ensures safety and sanitation. Yamazaki Baking adopted the American Institute of Baking (AIB) licensed food safety training and inspection system in around 2000, prompted by a spate of food tampering incidents at Japanese food makers. In addition to training and inspections by outside auditors once every two years, Yamazaki Baking plants now regularly conduct voluntary audits and take steps to reinforce safety measures to prevent tampering.

It was as part of these efforts that the company changed the specifications for holding film bread bags closed from using conventional plastic bread clips to fully sealing bag tops. This meant major changes in packaging processes, including having the packaging manufacturer develop an appropriate film and installing new equipment at plants across the nation. Nonetheless, Yamazaki Baking went ahead with these changes to further improve its food safety and sanitation with the aim of fulfilling its responsibility as a company that produces food products for the nation’s tables.

is crispy on the outside and fluffy inside.

the Royal Bread Premium, Royal Bread,

Cho-hojun and other Yamazaki Baking

shokupan lines.

plant to supermarkets, convenience

stores and other retailers.

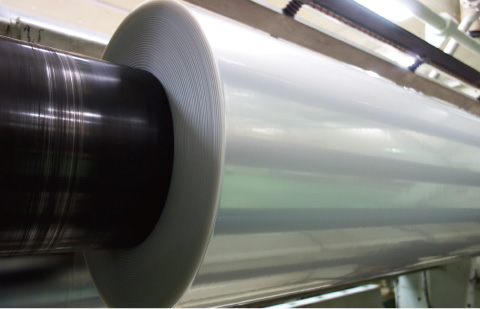

Supplying DIFAREN multilayered packaging film for bread and other products

DIC supplies DIFAREN packaging film, which underpins the safety of Yamazaki Baking’s bread loaves. This film harnesses an advanced compounded technology that incorporates compounding and multilayer thin-film formation technologies accumulated over the Company’s many years as a comprehensive manufacturer of fine chemicals. The multilayered structure of the film not only envelops loaves but also delivers a wealth of performance features critical to shokupan packaging. Because it is made with moisture-proof polypropylene thermoplastic resin, DIFAREN also safeguards against dryness, thus helping to maintain a fresh taste.

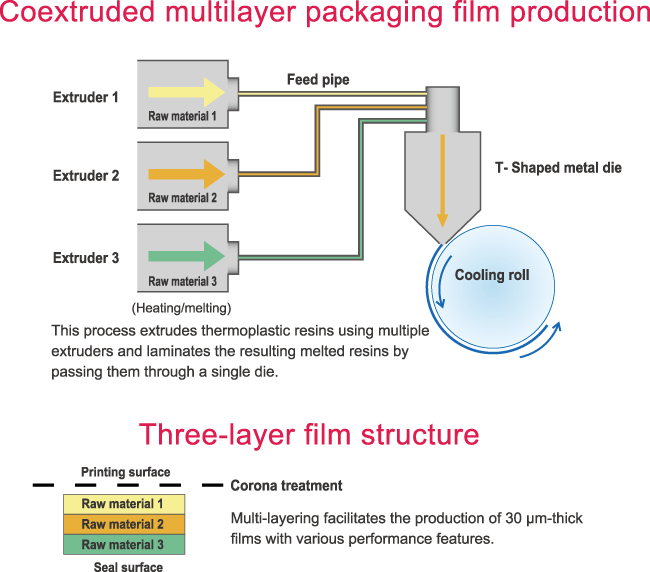

“DIC uses a process called coextrusion that simultaneously extrudes thermoplastic resins using multiple extruders and laminates the resulting melted resin by passing them through a single T-shaped metal die,” says Yasushi Watanabe, manager of the Coating & Applied Materials Technical Department’s Packaging Materials Technical Group 1, explaining the technology used to yield a multilayer film that is a mere 30 µm (0.03 mm) thick. “In 1970, DIC became the first company in Japan to manufacture and sell coextruded multilayer films, having introduced technology for coextrusion from the United States,” he continues. “Individual film layers are imbued with different performance features, including appropriate ink adhesion, sufficient strength for use in bags and suitability for use in packaging machines, which ensures stable filling. This ensures that DIFAREN will stand up well in all commercial bread packaging processes.”

A key merit of coextruded multilayer films is that it eliminates the need to laminate film layers together in a separate process. Because only one process is needed, DIC is able to supply film at a price that is affordable for use at plants that mass produce national shokupan brands.

Packaging for shokupan that

incorporates multilayered film is

easy to open yet maintains a

proper seal, thereby preventing

food tampering during distribution.

Easy-open feature delivers both excellent seal and convenience

Today, the tops of shokupan bags are sealed to prevent food tampering and drying. Joint development involving DIC, Yamazaki Baking and companies that process films into packaging led to the development of a multilayer structure for films, an achievement that assisted bread companies in responding to this change in packaging specifications.

“Packaging film is cut and simultaneously sealed using hot blades to transform it into bread bags,” says Mr. Watanabe. “Bread bags must protect their contents, so permanent seals must be strong. At the same time, the top seal needs to be easy enough for consumers to open. We experimented with resins used for inside surface layers that would make bags open easily at certain temperatures. This enabled us to strike a balance between bag strength and easy opening.”

The addition of such features that enhanced convenience made it possible to create a bread loaf packaging film design that is easy for anyone to open, including seniors and children, thereby making it compatible with the tenets of universal design. However, because this film must be produced at a width of several meters, advanced technologies—for, among others, simulating resin flowability for individual layers—are needed to ensure an even thickness. Accordingly, production, quality assurance and technical units work together to ensure consistent quality control. DIC engineers are stationed at film production facilities to advise swiftly in the event of quality issues. At the same time, DIC’s technology unit maintains the same bag and packaging machinery as customers, enabling it to conduct regular assessments. This approach allows DIC to confirm actual usability, rather than relying on data alone, and to provide feedback to production sites, thereby contributing significantly to the effort to ensure consistent quality.

coextruded films, which are produced at a width of several meters,

by matching the flowability of resins in each layer and optimizing equipment.

Realizing a Film for Bread Packaging Comprising Multiple Layers with Different Performance Features, that is Easy to Open and a Mere 30 µm Thick.

customer-requested dimensions.

Pursuing sustainable product development

The final question DIC Plaza had for Mr. Watanabe was what sort of new value he sees being added to DIC’s coextruded multilayer films going forward. “To date, we have sought to add value for film packaging from multiple perspectives, including by introducing new design features, such as matte and pearskin finishes, as well as by further enhancing performance and safety. Looking ahead, we will not only work to improve existing functions but also undertake R&D to add value that contributes to sustainability, which we see as an important challenge in light of issues surrounding discarded post-consumer packaging film.”

Packaging for bread and other food products is just one of many applications for packaging films. Adding value that reduces the environmental impact of these films would have significant benefits for global society. DIC continues to conduct R&D aimed at developing new films, leveraging the Group’s technological capabilities, including those of the Corporate R&D Division, which is responsible for basic research.

Manager, Packaging Materials Technical Group 1,

Coating & Applied Materials

Technical Group

Yasushi Watanabe

Joined DIC in 1993. Has been involved in

the development of packaging film technologies,

particularly for bread, for 25 years. Also provides

technical support for production and quality assurance.